Gold-Covered Boarshead and Meat Paste Castles: Final Tailgate of the Semester Offers a Taste of Medieval Feasts

On Sunday, November 21, 2021, the Medieval Institute hosted its final 75th anniversary home game tailgate of the year: a rowdy, exciting harvest feast. As the large crowd of revelers dined on food both modern (hot dogs and hot chocolate) and medieval (cider and ginger cookies), Dr. Sarah Peters Kernan offered them a taste of the often familiar, often surprising food culture of late medieval Europe (1200-1500 CE).

Just like at medieval feasts, in preparation for a competition, Fighting Irish tailgaters dress in their team colors and gather in large groups under tents to enjoy conversation, music, and prayer; in late medieval Europe, just as at our tailgate, food was a central part of processions, tournaments, and ceremonies. The grandeur and splendor of these feasts would inspire even Notre Dame to think bigger!

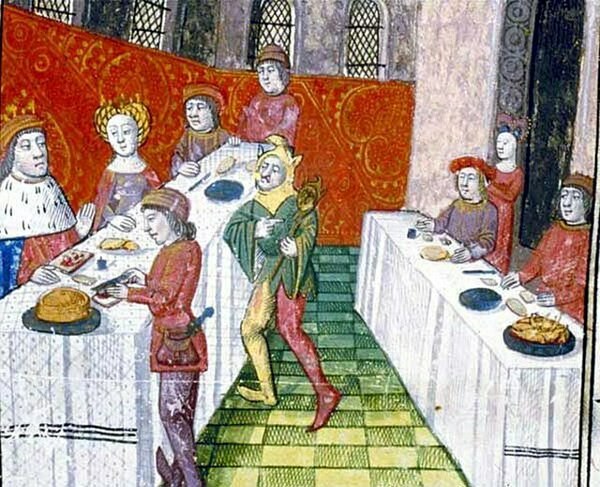

In the Late Middle Ages, feasts were for all of the senses, especially sight. Rose petals, saffron, and parsley would be used to dye food bright red, yellow or green, and chefs would create partially edible, multimedia food sculptures to decorate the table. These ranged from elaborate, like a swan or peacock roasted and then dressed in its own feathers, to extreme, like a boar's head covered in gold leaf with flaming sticks in its mouth or a meat paste castle next to a fountain of wine.

The meal itself had no real progression—every course would include a blend of sweet and savory foods served family style, and some of the combinations within dishes, like fish with fruit, would surprise modern palates.

Three-fourths of the written recipes that survive include spices, both botanicals familiar to modern American tongues (pepper, ginger, and, as they saw it, sugar) and less familiar (grains of paradise, galangal, and long pepper); cooks also added flavor and scent to their food with non-botanicals like ambergris, regurgitated from the digestive systems of sperm whales, and musk from the glands of deer.

The feasts themselves occurred in tents or grand halls, and could last for days on end with lavish entertainment like dancing, music, and theater. They were intended for a larger audience than the wealthy; non-eating spectators would come just to watch, and leftovers were distributed to the poor after the feasts as a forms of almsgiving.

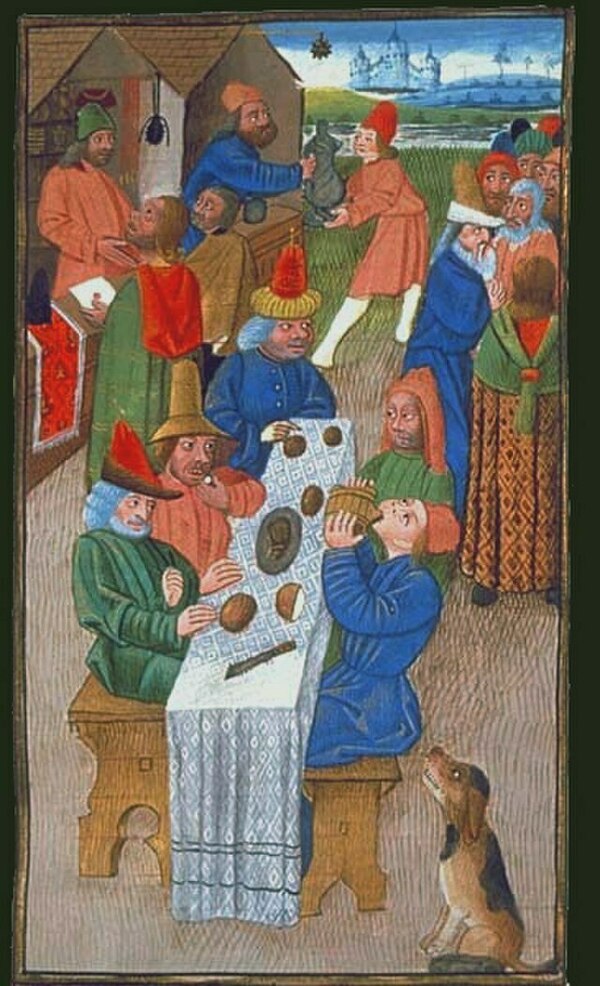

Of course, not every day could be a feast day, and tailgaters also got a view of daily eating in the medieval world. There, breakfast was not the most important meal, and it was more common for the manual laborers than the upper classes. A midday meal called dinner was the biggest of the day.

The food consumed at these meals was relatively similar to the present, with the exception of New World foods like beans, corn, and potatoes. Cereals like bread and ale made up 60 to 75 percent of medieval food consumption, and thin soups and hardy stews, fried foods like apple fritters, a variety of meats and fish, and the occasional fruit or vegetable filled out the diet.

Unlike the present, though, food culture was shaped by medical and liturgical considerations: food was an important way to balance the four humors of the body, and a stricter church calendar required Christians to eat no animal products for a full third of the year, rendering substitutions important: fish for meat, olive oil for butter, and almond milk for milk.

Tailgaters interested in trying their hand at medieval cooking at home could pick up packets with sample recipes at the back of the tailgate tent. You can try it too by cooking modern versions, such as hummus, chicken and rice, or fried apple fritters. You might also want to try some of these medieval recipes!

The crowd, listening while happily chowing down on a feast of their own, ate it up.