Alumni Spotlight: Rachel Koopmans

Prof. Rachel Koopmans on scaffolding at Canterbury Cathedral

Prof. Rachel Koopmans on scaffolding at Canterbury Cathedral

The Medieval Institute is pleased to present our spring 2019 Alumni Spotlight. In this series we feature the career paths of Institute alumni. Look for a new installment each semester, and follow our weekly news features regarding Medieval Institute-supported programming, events, guest lectures and general medievalist news on our news and events page.

This year’s spotlight falls on the award-winning scholar Rachel M. Koopmans. Prof. Koopmans studied at the Medieval Institute under the tutelage of John Van Engen. In 2001 she earned her Ph.D. with a dissertation entitled, “Dispute, Control and Individual Voice: The Making of Miracles at Christ Church, Canterbury, 1080-1220.” This dissertation formed the foundation of her first book. Koopmans is currently an associate professor at the University of York in Toronto, and her recent work on the stained glass of Canterbury Cathedral has earned her national attention in the United Kingdom and beyond.

We asked Prof. Koopmans about her work after the MI and her fascinating work on medieval stained glass.

What fascinates you about the Middle Ages? What interested you in Medieval Studies in the first place?

Detail of medieval pilgrims' boots from a Canterbury Cathedral window

Detail of medieval pilgrims' boots from a Canterbury Cathedral window

When I first started thinking about pursuing a Ph.D. in medieval studies, I liked the sound of it because it seemed so alien, mysterious, and long ago. It wasn’t much more sophisticated than that. I had next to no exposure to the Middle Ages in my K through 12 schooling. In my sophomore year in college, I had an inspiring medieval history course, and a history professor I liked a lot once told me that he wished he had become a medievalist. That stuck in my head. I grew up in a Protestant tradition in which history more or less began with the Reformation. I was curious about what came before that, especially by how medieval monasteries worked. I’ve always been intrigued by survival stories, and in comparison with how we live now, the Middle Ages is one big survival story. Just think about what it would mean to live in a period in which everything they owned was handmade, absolutely everything, including the pages of their books, the spoons in their hands, and the belts around their waists. I like thinking what [it] would mean to live in that kind of environment. Medievalists are blessed with a staggeringly long range of time and a huge geographical territory in which to roam. Trying to get a grasp on a whole millennium and continent is terribly intimidating, but it’s never boring. Even if you had dozens of careers, you could never explore it all.

I’m so grateful to the Medieval Institute and John Van Engen, my advisor, for giving me a “the sky’s the limit” mentality when it comes to research.

Tell us about your career path after graduating.

My career path is not one I would have been able to predict. After nine years in the M.A. and Ph.D. programs at Notre Dame, I started a tenure-track job at Arizona State University. Once there, I got to work transforming my dissertation into a book. That process took a lot longer than I had hoped. A couple of years into this work, when I had a semester off teaching funded by ASU’s Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, I had a eureka moment relating to the stained glass of Canterbury Cathedral. I had discussed this glass in the last chapter of my dissertation. While that was exhilarating and a turning point in my career, it eventually became apparent that the stained glass material wouldn’t fit into the book anymore. Through all this the tenure clock was ticking. To give myself more time, I applied for jobs and landed one in the history department of York University in Toronto, which is where I am now. When I was at Toronto, I finally finished the book manuscript. I had revised and reworked it so much it’s hardly recognizable as the dissertation project. It was published as Wonderful to Relate: Miracle Stories and Miracle Collecting in High Medieval England by Penn Press in 2011 and won the 2012 Margaret Wade Labarge prize from the Canadian Society of Medievalists.

Pilgrim panel on lightbox

Pilgrim panel on lightbox

Meanwhile, in 2007, the summer of the first year I was in Toronto, I went on an NEH summer seminar in York in the U.K. It was entitled “Cathedral and Culture in Medieval York” and led by Paul Szarmach and Dee Dyas. This seminar was a pivotal experience for me. I will always be grateful to Paul, Dee, Judy Frost (who helped coordinate the program), and the other wonderful scholars who attended and participated in the seminar. While there, I became deeply interested in a set of early sixteenth-century stained glass panels picturing legends relating to Thomas Becket in St Michael-le-Belfrey, a parish church in York. When I had my first sabbatical, in 2010, I chose to go back to York. This gave me the chance to bombard my long-suffering friends and colleagues who specialize in stained glass there with endless questions, and they generously gave me grounding I needed to come to terms with the technical aspects of studying medieval glass. While on that sabbatical, I finished my work on the Belfrey glass. At the conclusion of that sabbatical, with my book published, and tenure secured, I could think about pursuing that long-ago eureka moment.

The next stage was my application for a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) grant from the Canadian government for work on Canterbury’s “miracle windows,” so-called because they picture dozens of the posthumous miracles of Thomas Becket. Three of the chapters of the Wonderful to Relate book are focused on the Becket miracle collections. What I had realized back in Arizona was that some of the glass narratives of Becket’s miracles had been tied to the wrong stories. For example, a pair of panels that was long thought to connect to the story of an Augustinian prior of Oxford actually pictured the healing of a local knight of Canterbury. At the time I thought about one out of five of the glass narratives had been misattributed, though now I think it’s probably more like one in three. As I argued in my grant application, these misattributions skew how one sees the entire sequence, and as some of the earliest and most important stained glass to survive in England, the miracle windows were worthy of a major new study. The SSHRC committee thankfully agreed with me and gave me the money for a five-year study of the windows, work which was to include a translation of the glaziers’ chief source text, Benedict of Peterborough’s Passion and Miracles of Thomas Becket, written ca. 1171-73.

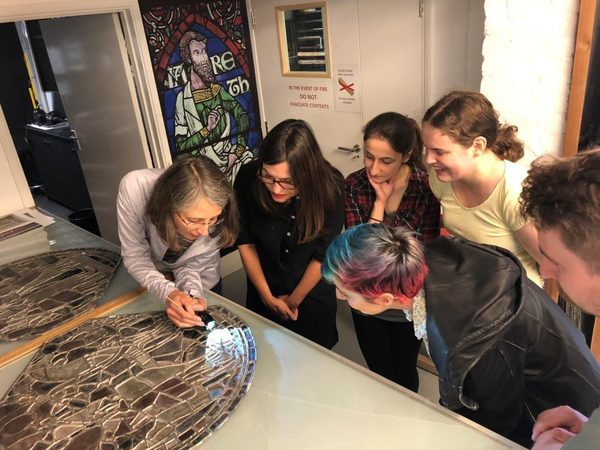

Prof. Koopmans showing glass to MEMS students, Sept 2018

Prof. Koopmans showing glass to MEMS students, Sept 2018

The SSHRC grant, awarded in 2012, gave me the funds to spend my summers and a second sabbatical, in 2016, in Canterbury. I spent a lot of this time in the cathedral’s archives working methodically through everything I could find relevant to the miracle windows. Unfortunately, there is nothing about the glazing or medieval reception of the windows surviving in the archives. However, what I had learned from my friends in York was the utmost importance of coming to grips with the extent of modern restorations and repairs in a medieval window. Art historians had already plowed through some of the material in Canterbury’s archives on nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century repair work, but a lot of it, I found, was untouched, including the papers of a woman who wrote the first guidebook to Canterbury’s stained glass in 1897. The SSHRC grant gave me the means to immerse myself in Canterbury’s archives in the summers, and when I was back in Toronto and teaching, I would work on articles and on my translation of Benedict’s collection. The latter is, I’m pleased to say, quite close to completion now.

I find it especially gratifying that my research, started on the Hesburgh Library's seventh floor, is beginning to have an impact on the experience of the hundreds of thousands of visitors who tour Canterbury Cathedral every year.

I was able to spend six months of my 2016 sabbatical in Canterbury. It was during this time that I came to know the head of Canterbury’s stained glass conservation studio, Leonie Seliger, quite well, and I would come to her with questions (many questions!) about the miracle windows. I was finding so much in the archives, including material that was making me query what I was reading in the standard catalogue of Canterbury’s glass. I had known for years that there were problems with the attributions of the glass narratives to particular stories in the medieval texts, but now I was turning up evidence that suggested that the catalogue’s assessment of how much medieval glass remained intact in the miracle windows might also be in error.

Leonie and Prof. Koopmans working at Canterbury Cathedral

Leonie and Prof. Koopmans working at Canterbury Cathedral

In the summer of 2017 I brought some of this evidence to Leonie, and she was intrigued enough to seek permission and the funds to remove the glass from one window for close examination. This past summer, July to September 2018, the glass was removed from the window (numbered nV) and taken to the conservation studio. After so many years of looking at the glass from the floor of the cathedral and via photographs, it was an absolutely marvelous experience to get to see and analyze it close up. Leonie looked at every piece of glass within the panels—something like two thousand pieces in all—to determine what was an original medieval piece and what was a modern replacement. We found that two panels that had been dismissed as having been made up by a late-nineteenth-century glazier in fact had so much original medieval glass intact that there is no doubt they are medieval creations. One of these is the earliest known depiction of pilgrims on the road to Canterbury, and the discovery generated considerable media interest, with reporters from the BBC, ITV, Channel 4, and the Times covering the story. I never thought that I would be part of something so exciting. Every panel we examined yielded new discoveries. You can read, for example, about our analysis of a panel showing demons attacking a sleeper in bed.

How has your interdisciplinary training from the Medieval Institute (versus, say, a Ph.D. in History) benefited you?

I think it’s obvious from my career path that my interdisciplinary training from the Medieval Institute has made me who I am as a scholar. It has given me the courage to go through any research door that I see standing open, whether or not I have the formal credentials to do so. My Wonderful to Relate book is shelved alongside books in literary studies, the PRs [the designation for English Literature in the Library of Congress Classification]. My catalogue of Canterbury’s miracle windows will be in the NKs [Decorative Arts]. It’s likely the book after that will be in an entirely different part of the library again, maybe the DAs [History of Great Britain], or possibly the TXs [Home Economics], because I’m becoming more and more interested in food history. There’s nothing preventing a Ph.D. in History from venturing into different fields, but I do think your graduate training is very formative in setting your intellectual horizons. I’m so grateful to the Medieval Institute and John Van Engen, my advisor, for giving me a “the sky’s the limit” mentality when it comes to research.

What are the next stages of your current research?

Glass removal from Canterbury Cathedral windows, July 2018

Glass removal from Canterbury Cathedral windows, July 2018

The main scholarly publication resulting from my work on Canterbury’s glass will be a revised catalogue of the miracle windows in the Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi series. This new catalogue will include new descriptions, restoration charts, and photographs of all the panels in the miracle windows. To achieve this, we will have to have the glass from the remaining seven windows in the sequence out for the same kind of close examination we did in the summer of 2018. It costs a great deal to erect scaffolding and pay for the time of the glaziers to remove and reinstall the glass, and we also want to address some urgent conservation needs with the windows as well. The examination on the first window was funded by the Friends of Canterbury Cathedral, for which we are most grateful, but while they will, we hope, contribute to the next phase of the project, the whole of it will be out of their price range.

Looking for donors, seeking permission for the removal and conservation of medieval monuments, and giving public lectures to raise enthusiasm about a project were not things I anticipated doing when I was a graduate student. I didn’t think I would have to sweet talk anyone to do my work except maybe a recalcitrant archivist—or maybe an associate dean or two! But it is my training at Notre Dame that got me to this point. I find it especially gratifying that my research, started on the Hesburgh Library's seventh floor, is beginning to have an impact on the experience of the hundreds of thousands of visitors who tour Canterbury Cathedral every year. I am currently writing a new guidebook on the window we examined this past summer for the use of guides and visitors. When our work is finished, I intend to publish a more comprehensive guidebook that will make the whole of that marvelous glass more accessible to visitors to Canterbury and to undergraduate students as well. You never know where a degree in medieval studies might lead!

Editor's note: interview responses have been edited for length and clarity.