Medieval Cheesemaking with Leslie Lockett

In Fall 2018, the Medieval Institute published an Alumni Spotlight feature on alumna Leslie Lockett. Lockett received her Ph.D. from the MI in 2004, writing her dissertation on “Corporeality in the Psychology of the Anglo-Saxons” under the direction of Michael Lapidge and Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe and is currently Associate Professor of English and Associate Director of the Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at The Ohio State University. What not many people know, however, is that in addition to her specialties in Old English and Latin literature as well as early medieval intellectual history and manuscript studies, Lockett, an undergrad Biology major, has a strong interest in medieval cheesemaking. We present here some outtakes from Lockett's original Alumni Spotlight in which she illuminates both the process of cheesemaking in the medieval period as well as medieval cultural attitudes towards cheese.

Tell us about your research on early medieval cheese making. Is that connected with your past in biology?

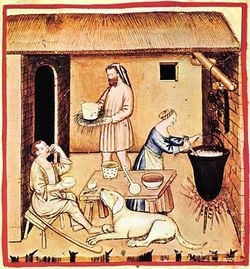

It is, especially the direction it has taken in the last couple of lectures I have given. I haven’t published anything on this yet, but have been giving papers on it for over a year. I feel hesitant because I am turning a hobby into academic work. I like approaching it from a textual point of view, and then illuminating what’s going on biologically in cheese-making. I mean cheese is basically like a bacteria farm, right? And the good flavors that come out of cheese are made by having the right levels of different bacteria and fungi in your cheese. Most people who know about the biological side don’t know the texts and vice versa. I have a really fun time putting them together.

Are there special blessings for food and for bread and cheese?

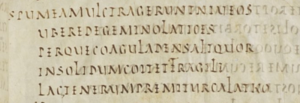

There are. Notker has a blessing for bread and cheese. Prudentius has a great hymnal poem for before eating written in very florid language. He writes this insane description of milking the beef to get the milk. Cassian is one of the people who writes about the milking part too. There is also biblical exegesis, like in the book of Job: “hast thou not milked me like milk, and curdled me like cheese?” That’s a really weird thing for Job to say to God. In essence, the mechanism by which curds and whey separate was invisible.

People could make it happen by adding rennet or adding a plant protease, but they didn’t know how it worked since they didn’t have microscopes. So, it was regarded as an analogy for the hand of God coming in and consoling the child in the womb. Because it is so ineffable, “hast thou curdled me like cheese” takes the divine aspect of the formation of the new human being. Basically, any human can do the milking; that’s like sexual reproduction. Then, the curdling of the cheese, that’s where God puts His hand in and you can’t know how it happens. That’s in a few of the early Latin Fathers who comment on Job. There’s also this weird other trajectory of that same kind of image that runs from Aristotle through some of the early Fathers to Hildegard of Bingen, and, weirdly, it survives in modern Basque culture, the cheese metaphors for conception and fertility.

When I’m lecturing on this stuff now, it’s mostly from the angle of the Anglo-Saxons’ cultural attitudes toward cheese, which is complicated. Fresh cheese is a seasonal food to celebrate, but once cheese was out of season, they seem to have been able to make aged cheeses that were stable and safe, but not tasty. I’m wondering why this is not the case in nearby Ireland, where there was a very well-formed culture of appreciating cheese and thinking of it as an honorific or cultured food.

I’ve been exploring whether it’s possible that the cheese makers' ability to micromanage the microorganisms was thrown off by recent migration from a different territory, and then by the climatic minimum that set in around 526 and lasted until the early Carolingian period, which would have altered the conditions. The climatic minimum is similar to a little ice age: a lot of bad weather, not optimal growing conditions. The initial, major event was in 526, but things didn’t start to upswing again until the early ninth century.

At any rate, when you’re dependent on ambient bacteria, not on artificially refrigerated or heated buildings and factory-made cocktails of bacteria that you put in the milk, and other factors that you can’t see and can’t control, your cheese would be subject to being totally messed up by changing environmental conditions. I’m hoping that I’ll be able to do some sort of interdisciplinary project with someone who specializes in environmental history or experimental archeology who can help me figure out whether this hypothesis is remotely feasible or not.

Editor's Note: This interview was conducted by Brandon Cook with editing by Dov Honick.